More fascinating investigations from our artist in residence David Chatton Barker…

Peat in Brief

Peat forms when plant material does not fully decay in acidic and anaerobic (absence of oxygen) conditions. It is composed mainly of wetland vegetation: principally bog plants including mosses, sedges, and shrubs. As it accumulates, the peat holds water. This slowly creates wetter conditions that allow the area of wetland to expand. Peatland features can include ponds, ridges, and raised bogs. Most modern peat bogs formed 12,000 years ago in high latitudes after the glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age. Peat usually accumulates slowly at the rate of about a millimetre per year. Depending on the agency, peat is not generally regarded as a renewable source of energy, due to its extraction rate in industrialised countries far exceeding its slow regrowth rate of 1 mm per year!

Film in Peat

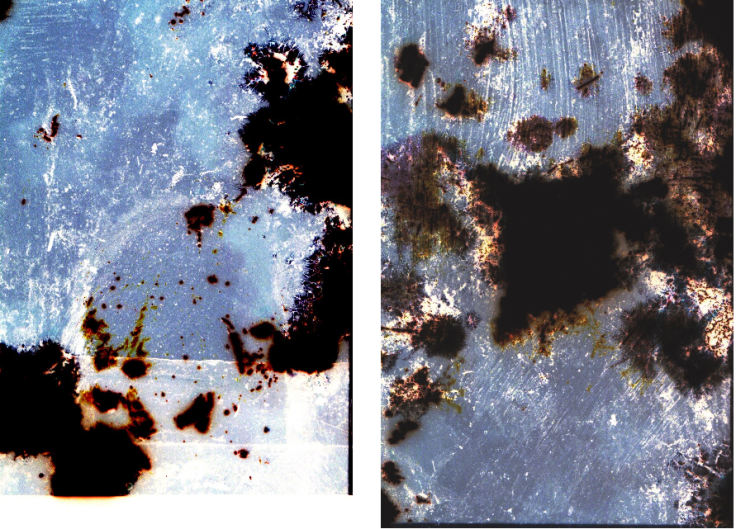

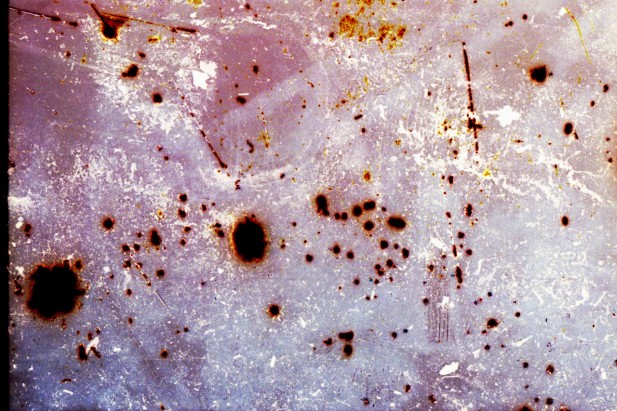

Over the past two months a series of 35mm photographic negatives taken of Brown Wardle Hill have been laying buried in peat, several inches below the surface of the hill. Having experienced the best of winter’s conditions these negatives were recently excavated and left to be cleaned by the rain on a washing line. The resulting negatives have been scanned and a selection presented here as part of an ongoing investigation into the botanical-chemical reactions between analogue film and the earth’s substratum over varying periods of time. This process offers up a way of thinking and interacting with deep time (the concept of geologic time) and the way in which the earth’s geology is a slow organic environmental process, having fascinating results both aesthetically and metaphysically to our eyes and minds. The results from this two month exposure to the waterlogged peat has rendered the original imagery totally abstracted, an explosion of alchemical cosmic lichen patterns… newly revealed hidden landscapes to get lost in.

BWH PEAT negative 1 and 2

BWH PEAT negative 3,4, 5 and 6

Peat Fire & Pigments

Peat has a high carbon content and can burn under low moisture conditions. Once ignited by the presence of a heat source (e.g. a wildfire penetrating the subsurface), it smoulders. These smouldering fires can burn undetected for very long periods of time (months, years, and even centuries) propagating in a creeping fashion through the underground peat layer.

I recently found a passage within a book surveying the landscape around Whitworth which mentioned a peat fire removing much of the rich vegetation thriving on the moors and on Brown Wardle Hill.

‘The peat fires which swept the whole of the moors surrounding Whitworth Valley in the draught of 1921, caused much denudation from which the area has never really recovered. According to Mattley, Brown Wardle Hill which is due east of the boundary at 1,322 ft o.d was once covered with luxuriant heather, whimberry and bilberry, broom and gorse. Moor fowl were large and plentiful, hares and rabbits, foxes and badgers ran about the area in profusion. The fourteen week fire destroyed all this and although some heather, sparse grasses, rabbits, hare and a few fox have returned, the area hasn’t yet recovered, some 50 years later.”

1.Mattley, R.D Annals of Rochdale. James Clegg, The Aldine Press 1899.

This fairly common natural disaster seems particularly pertinent to our time, given the recent fires over the Lancashire moors. As a creative interpretation of the Brown Wardle Hill peat fire and the ecological reality of such disasters I created a pigment* using peat and illustrated the four ‘lost’ plants in a typical Victorian botanical fashion.

*Pigment box using stones, coal, sand and peat found on Brown Wardle Hill

In his comprehensive gazetteer Rochdale and The Vale Whitworth (Its moorlands, favourite nooks, green lanes, and scenery), William Robertson also speaks of Brown Wardle and the surrounding moors being “Luxuriantly covered with whimberry bushes, cranberry bushes, heath and rushes… the pasture land was divided by thorn hedges; and a large number of birch trees; the ‘the lord of the woods,” the long-surviving oak; the mountain ash, and the waving pine grew in the hedgerows. On the banks were wild strawberries, raspberries, primroses, blue-eyed violets and cowslips. He also mentions a fire, but one of human design. ‘The heath on the moorlands being set fire by mischievous persons, all were destroyed, and walls and stone flags had to be adopted.”

Peat pigment, botanical drawings by artist, on watercolour paper

Peat pigment, botanical drawings by artist, on watercolour paper

Peat in Archaeology

Archaeologist and North West Projects Manager for Dig Ventures, Stuart Noon, offers up a fascinating insight into the importance of peat within archaeology and the landscape of the South Pennine Moors:

Peat has remarkable archaeological potential. In their undisturbed state at least, peat bogs are oxygen-free environments due to their saturation. These conditions are hostile to the microbes and fungi that would normally decay organic material such as the remains of plants, which are the principal constituents of the peat. The same anoxic conditions also offer protection from decay for organic archaeological remains. The vast majority of objects and structures used by our ancestors were made from organic materials (in particular wood). These are normally lost on dryland archaeological sites but can be pre served in peatlands.

served in peatlands.

Peat is immensely valuable as archives of past environments (palaeoenvironments). The manner in which peat accumulates means that the deposits have stratigraphic integrity, meaning that contained within each layer can be found macroscopic and microscopic remains of plants and other organisms that shed light on landscape change and biodiversity on timescales ranging from centuries to millennia. The high organic content of peat means that these records can be dated using the radiocarbon method.

The saturated conditions mean that even soft tissue can survive, including both skin and internal organs. Probably the best known archaeological finds are the remains of ‘bog bodies’ such as the famous prehistoric Tollund Man in Denmark, Lindow Man in the UK, or the more recent Irish discoveries of Clonycavan Man, Old Croghan Man and Ireland’s oldest known bog body, Cashel Man, dated to the Bronze Age.

Peat is immensely valuable as archives of past environments (palaeoenvironments). The manner in which peat accumulates means that the deposits have stratigraphic integrity, meaning that contained within each layer can be found macroscopic and microscopic remains of plants and other organisms that shed light on landscape change and biodiversity on timescales ranging from centuries to millennia. The high organic content of peat means that these records can be dated using the radiocarbon method.

Peat is immensely valuable as archives of past environments (palaeoenvironments). The manner in which peat accumulates means that the deposits have stra tigraphic integrity, meaning that contained within each layer can be found macroscopic and microscopic remains of plants and other organisms that shed light on landscape change and biodiversity on timescales ranging from centuries to millennia. The high organic content of peat means that these records can be dated using the radiocarbon method.

tigraphic integrity, meaning that contained within each layer can be found macroscopic and microscopic remains of plants and other organisms that shed light on landscape change and biodiversity on timescales ranging from centuries to millennia. The high organic content of peat means that these records can be dated using the radiocarbon method.

The best known such records are probably pollen grains which provide evidence of past vegetation change. But evidence from other organic material can be used to reconstruct other past environmental processes. For example, single-celled organisms called testate amoebae, preserved in sub-fossil form, are highly sensitive to peatland hydrology and have been extensively used in recent years to reconstruct a history of climatic changes.

The potential of bogs to preserve both environmental and archaeological records means that they can be regarded as archives of ‘hidden landscapes’. The accumulating peat literally seals and protects evidence of human activity ranging from the macroscopic (in the form of archaeological sites, artefacts and larger plant and animal remains) through to the microscopic (pollen, testate amoebae and other remains) material that provides contextual evidence of environmental processes.

There has been extensive study of the palaeoenvironmental record from bogs and notable archaeological excavations of sites and artefacts, but there have been relatively few concerted attempts to integrate these approaches. In part this is because generating sufficient data to model the development of a bog in four dimensions (the fourth being time) is a formidable research challenge (https://phys.org/news/2018-09-bogsunique-history.html#jCp).

Lancashire and Greater Manchester has one of the highest concentrations of Mesolithic (c8000-4000 BCE) findspots in Britain known to underlie Holocene upland peat in the area (Cowell 1996, 21). It has been documented for over a century that lithic-artefacts can be found at the edges of eroding peat haggs on the high Pennine moorlands (Law and Horsfall 1882). The majority of artefacts have been recovered at the edge of patches of peat or in areas where erosion has exposed the original land surface. Very often the flints have been found within the peat, indicating that peat was already beginning to form by the Mesolithic period (Switsur and Jacob, 1975). Mesolithic sites are principally sited on hilltops and south-facing slopes, in areas providing good visibility and natural shelter overlooking spring-heads and water sources above the tree line around 360m (B Pearson, J Price, V Tanner and J Walker. 1981). From around 5000 BCE onwards, the tree canopy appears to have given way to scrubland, with patches of peat and grassland which would have been attractive animal species such as red and roe deer, aurochs or wild cattle, and wild pig and therefore to human-hunting groups (Barnes 1982, 86).

The peat deposits of the Spodden Valley area are of particular palaeoenvironmental interest possibly containing palaeobiological remains (pollen, insects, plant material etc), which could yield information about past climate, vegetation and land-use change. They also have the potential to preserve organic structural remains if waterlogged. During the late Mesolithic period mixed deciduous forest in the Rochdale area is indicated by pollen samples taken from sites at Dean Clough I, which yielded a radiocarbon date of 5645 +/- 140 bce (Barnes 1982, 86).

Neolithic arrow found on Brown Wardle Hill, circa 1897

Mesolithic artefacts on Crook Moor derive from horizons, dated c. 8300-5000 BC, sealed under the blanket peat (CFA Archaeology 2013). An excavation prior to a wind farm development on Scout Moor, including Knowl Moor, revealed evidence of probable birch tree remains within the peat indicating that they were growing at the point of peat inception, but the date of this is unknown (OA North 2005).

The need for sampling cores through peat deposits has recently been identified in the Prehistoric Agenda Update for the North West. As is the need to better understand the distribution of prehistoric archaeology across the landscape along with the changing nature of the relationships between people and their environment during the prehistoric period and to examine existing archives to identify Mesolithic type sites (Ibid).

David’s investigation continues and if you press the Follow button for this blog you will receive an email letting you know when there is a new post.